This was part two of a planned three-part series on Art, Race & Real Estate in New Orleans for a periodical called The Shotgun, which has since vanished from the web.

In part one of this series we talked about two recent racist New Orleans art swindlers: the AirBnB Queen, Muck Rock, and the deranged daughter of Pontalba prosperity, Ti-Rock Moore, who it appears had a hidden history as a crooked cosmetic dentist.

But rest assured, the metaphorical multimedia menhirs mounted by Muck Rock and Ti-Rock on our Artster Island stand atop a fundamental bedrock of bullshit laid by Kirsha Kaechele. Kirsha was the template, the original terrible vapid criticism-proof white lady artist rampaging through post-flood New Orleans. She’s a canny enough scammer that she’ll likely persist after all the simulacra she prefigured wither.

Another thing that sets Kirsha apart is that her “art” was– non-figuratively, non-ironically, non-metaphorically– the performative destruction of New Orleans housing stock.

If you’ve always been handed whatever you want, being told “No” is strange and exciting. So like any spoiled white adventurer, Kirsha Kaechele was attracted to the forbidden. After showing up in New Orleans and being warned not to ride her bicycle through St. Roch, she told an interviewer, “I was curious. I rode my bike over there, just meekly, one block in, and rode back. That one block was electric. I just loved it. There were people sitting on their stoops and the vibe was completely different. It was all black, and it was just vital. People were yelling across the street at each other. I loved it. I did that a couple more times over the next few months and then decided I wanted to buy a place.”

But why just buy one place in St Roch when you can buy five? “I had an inheritance,” she confided in Elizabeth Pearce, one of her current husband’s employees, during a less-than-confrontational long-form 2016 interview in which Kaechele revealed that rich men, beginning with her father, had supported her entire life. Not only did this underwrite her real-estate acquisitions, but it gave her a big advantage as a “professional” artist, since it’s never mattered if anyone liked her work enough to pay for it. “Occasionally there’ll be a transaction,” Kaechele said. “I sold my car once, but then I never cashed the check. Going into a bank is such an aesthetically void experience.”

She characterized the idea of making an object as art and selling it as “totally repulsive.”

Plenty’s been written about her antics– a 2014 Lens interview by Ariella Cohen covers much of the locally relevant backstory– but the short version is that after the failure of the federal levees, Kirsha offered up a whole bunch of houses in St. Roch as playgrounds for some of contemporary art’s biggest names, including the legendary conceptual artist Mel Chin. Celebrity “creatives” from London and New York City transformed what had been working-class New Orleans housing stock into showcases for the cutting edge of contemporary art, turning a big chunk of post-Katrina North Villere St. into an art installation.

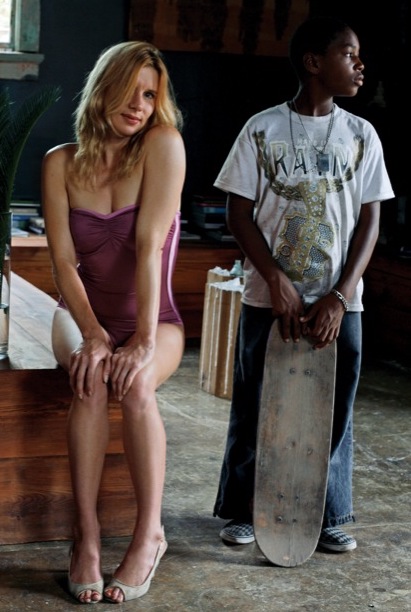

In 2008 Kaechele took over the whole street to host an outdoors “block party” dinner event (entry price: $250) for celebrities like Uma Thurman. The resultant visuals– glittering white wealth in a disaster-wracked Black neighborhood– thrilled the cosseted, marcescenct grandees who perch atop the so-called art world. International publications covered the event approvingly.

“It was a beautiful party in the middle of complete destruction,” Kaechele told Interview magazine. “It was so inspiring, and that created momentum. Part of what made the project such a success was this perception that it was a symbol of the rebirth, a.k.a. the colonization of these ghetto neighborhoods by bright, young white people.”

“It was a beautiful party in the middle of complete destruction,” Kaechele told Interview magazine. “It was so inspiring, and that created momentum. Part of what made the project such a success was this perception that it was a symbol of the rebirth, a.k.a. the colonization of these ghetto neighborhoods by bright, young white people.”

I’ve been told I use the word “racist” too much in my writing. I don’t know, though, that shit there just sounds so racist to me. As all this unfolded, NOLA.com’s longtime trudging arts mule Doug MacCash filled a now-familiar cheerleader role, upending vats of avuncular encomium over Kaechele and the big-shot important artists she enticed to our backwater.

Despite her own words revealing her as merely a blithe bipedal feculence– not human but rather a sinister, soulless publicity-hungry taxidermy of the Contemporary Artiste, a carefully conditioned skinpouch stuffed with wads of formaldehyde-soaked cash– Kirsha does have her defenders. Dribs and drabs of the millions of unearned dollars sluiced into her unremarkable person seep out, ensuring she’s in every exercise attended by sycophantic lappers of this tasty financial sweat.

Like many unacquainted with the value of a dollar, Kirsha could be generous. “After Katrina,” a friend of hers told me, “Kirsha opened her house on Villere to the neighborhood. Mostly she was hosting free classes, field trips and other art activities for the kids that lived around her. She lost a laptop a week doing this, but just kept on inviting strangers into her home.”

She lived comfy out there in St. Roch, a gleaming blonde goddess posing for endless pics among the non-blonde children. This was what the horror and tragedy of the federal levee failure meant to people like her, as it did to all the Charter School mavens and subsequent entrepreneurs: New Orleans wasn’t a real place, just a laboratory, a dollhouse, a colorful backdrop for the hijinks of the rich.

In a fawning 2009 interview by Generic Art Solutions’ Tony Campbell, Kaechele admitted some of her housing-turned-art-installation “gutter-punk” neighbors “are not appreciating the international art world element that I’m introducing to the neighborhood! I think it makes them uncomfortable.” Kaechele had one young woman jailed for spray-painting graffiti on the expensive art.

Tony Campbell’s own work can be described as “AdBusters without critique.” He and his creative TweedleDee Matt Vis poke gentle, loving fun at the foibles of art’s inner circle, being sure not to hurt anyone’s feelings or say anything substantive. This is ten rent districts away from the iconoclasm of the Guerilla Girls or the Yes Men; Generic Art Solutions doesn’t provide a mirror for the art world, just a flattering insta filter. Since the art world loves itself, GAS has had some success. Campbell, in his affectionate profile of Kirsha, grumbled about a “spate of attacks” by locals on the important art works Kaechele had brought to St Roch; he was of the opinion that whoever had used a sharpie to tag Damien Hirst’s $3,000,000 pickled sheep was merely “a disgruntled artist looking for some attention.”

Locally, most who remember Kaechele don’t remember her art but its aftermath. In 2010, Kirsha left town and the art left too, abandoning the neighborhood she’d crowed about loving so much. The interiors of the houses-turned-galleries gaped open to the air where the artists had removed structural “art” elements; left behind were just the worthless, rotting and now unsavable remnants of homes in which generation of New Orleanians had lived and raised families. In the words of MacCash’s slightly less infatuated colleague Robert McClendon, “She became infamous in the wider New Orleans community when she moved to Tasmania, left the houses to rot and stopped paying property taxes.”

Neighbors couldn’t reach her; the houses spawned rats and termites, permanent decaying eyesores in a neighborhood struggling to rebuild. In April 2011 Kaechele, then dating a Tasmanian multimillionaire, regretfully assured a still-sympathetic MacCash she couldn’t pay her taxes and liens and couldn’t remediate the blight she’d inflicted on St. Roch.

Despite all this financial hardship, when the Prospect 2 art biennial came to New Orleans a few months after that interview, Kaechele’s “Life is Art” foundation managed to scrape together enough pennies to rent a series of billboards along St. Claude Ave and adorn them with playful photos of Kaechele in an off-the-shoulder cocktail dress.

The particular parasites who’d swarm in for the “Prospect” exhibitions were the target audience for these billboards because they’re the only people worthy of a response from Kaechele; she’s never given a shit what anyone else thought. This is something too many peasants outside the inner circles of capital-A Art don’t understand: the reason so much contemporary art seems meaningless or incomprehensible is that it isn’t meant for us. It’s only a series of clever remarks in a private conversation (or more often, a pissing contest) among a tiny, elite group of rich cosmopolitan jet-setters. That doesn’t mean the rest of us aren’t obligated to support the art, to underwrite it, to praise and defend it– it’s very important art, after all– but our pathetic efforts to engage with the art or find something in it for ourselves is as funny and unnatural as dogs trying to walk on their hind legs.

Doug MacCash’s cautious coverage of Kirsha’s annoying billboards presaged his stubborn refusal to acknowledge that Muck Rock had painted the wrong Black man as Dutch Morial, an incident covered in Part I. According to MacCash, the Biennial billboards depicted “a young blonde woman in a black party dress that many onlookers identified as erstwhile New Orleans art celebrity Kirsha Kaechele.” Kaechele claimed no responsibility for the billboards, although Doug did say “she acknowledged the image looked like her.” That’s right, Doug: an image that looks like something. Far out!

MacCash’s gentle musings certainly didn’t make mention that less than a week before those billboards went up, one of the long-abandoned Kaechele houses burned to the ground in a four-alarm fire that injured a New Orleans firefighter and badly damaged five other neighboring homes, one of which, a double shotgun, was subsequently demolished.

Just a couple more housing units destroyed by carelessness; a couple more notches on Kirsha’s belt. Her “art” always centered on destroying New Orleans housing stock. This made her in many ways an ideal spiritual totem for the post-flood downtown arts scene, as subsequent years of St. Claude Gallery Night have seen more and more former homes converted into galleries showcasing the dilettante new owners’ talentless college friends.

Like most post-K artists with any measure of success, Kaechele quickly left New Orleans for greener pastures, retreating in early 2010 to a pot farm in California. We’ll learn more about that and in particular her special farm friend, wealthy weirdo John “Joahn” Orgon, in part three.

In 2013, Kaechele relinquished the only still-standing St. Roch house of the original five. It sold for $150,000. We learn from the New Orleans assessor’s office that its previous sale price was $2,421. That’s a tidy 60x markup; Kirsha finally found the courage to brave the banality of the banking sphere and cash a check.

A friend of Kirsha’s blames Doug MacCash for much of her bad reputation. According to this mutual friend, “no one has ever criticized Mel Chin… For some reason, Kirsha took 100% of the blame. I believe the reason for that is the same reason why Doug MacCash elevated her in the first place: she’s a woman. A pretty woman, whose photo looked good in the paper.”

Fair enough. Then what about Mel Chin, one of the biggest names in art, whose earnestly didactic St Roch “Safe House” installation sought to instruct, then destructed? In the online comments of a WNYC piece on Kaechele’s destruction of St. Roch housing, Chin strived to distance himself from her. He claimed Kirsha was merely “a curator and host” for his otherwise unaffiliated installation, “which was funded by Transforma Projects for New Orleans and the National Performance Network.”

Fair enough. Then what about Mel Chin, one of the biggest names in art, whose earnestly didactic St Roch “Safe House” installation sought to instruct, then destructed? In the online comments of a WNYC piece on Kaechele’s destruction of St. Roch housing, Chin strived to distance himself from her. He claimed Kirsha was merely “a curator and host” for his otherwise unaffiliated installation, “which was funded by Transforma Projects for New Orleans and the National Performance Network.”

That last name rang a bell. I’d first heard of the “National Performance Network” in January 2014 when they launched a massive makeover and takeover of 1024 Elysian Fields.

What does NPN do? According to its website, it “strengthens the management and community engagement capacities of NPN/VAN Partners and the artists they present.” My nonprofitese is rusty, but near as I can tell, NPN’s salaried staffers act as monetary middlemen between big corporations or foundations and the (formerly) independent artists whom those entities sponsor.

NPN taking possession of 1024 Elysian not only cost your humble scribe his writing space but evicted both the Lambda Center, a local queer substance-abuse recovery organization, and Plan B Bikes, a volunteer community bicycle collective that had been providing no- and low-cost bicycles to New Orleanians for 14 years.

It’s tough to find space in New Orleans, but the Lambda Center managed. Plan B, which had been similarly displaced back in 2011 when 511 Marigny was redeveloped from a community center into condos for yuppies, never reopened.

Seems like a shame, but we all must make sacrifices for art.

All of this is art– the art of the deal, the muralist decorating the redeveloped $1400 warehouse one-bedroom, the art deliriously celebrating its own cleverness while destroying and supplanting the homes of the poor.

It’s the word “art” as spoken by Sean Cummings when he’s wooing wealthy condo shoppers, the word as it appears in metal lettering above the locked gate of a “community” space owned by Pres Kabacoff. Art as written in civic visioning documents by consultancies, art as inked into funding pitches by non-profits staffed by rich kids from elsewhere. Indeed, for those in this series, those like Candy Chang, Sean Cummings, Pres Kabacoff and Jeffrey Farshad, “art” is literally whatever wealthy people feel like doing with real estate; it’s the hand-waving shorthand for their passing whims, forming an inefficient, tourist-spectacular phase of systematic racialized displacement.

In the third and final installment of this series, we’ll spill the organic matcha tea on Kirsha’s triumphant return to New Orleans & get acquainted with some of the strange, secretive real-estate richies who’ve underwritten her follies. We’ll look at resistance to “art-washing” and the different ways even some broke, unfamous New Orleans artists enact complicity or resistance.

Illustration by vulpes